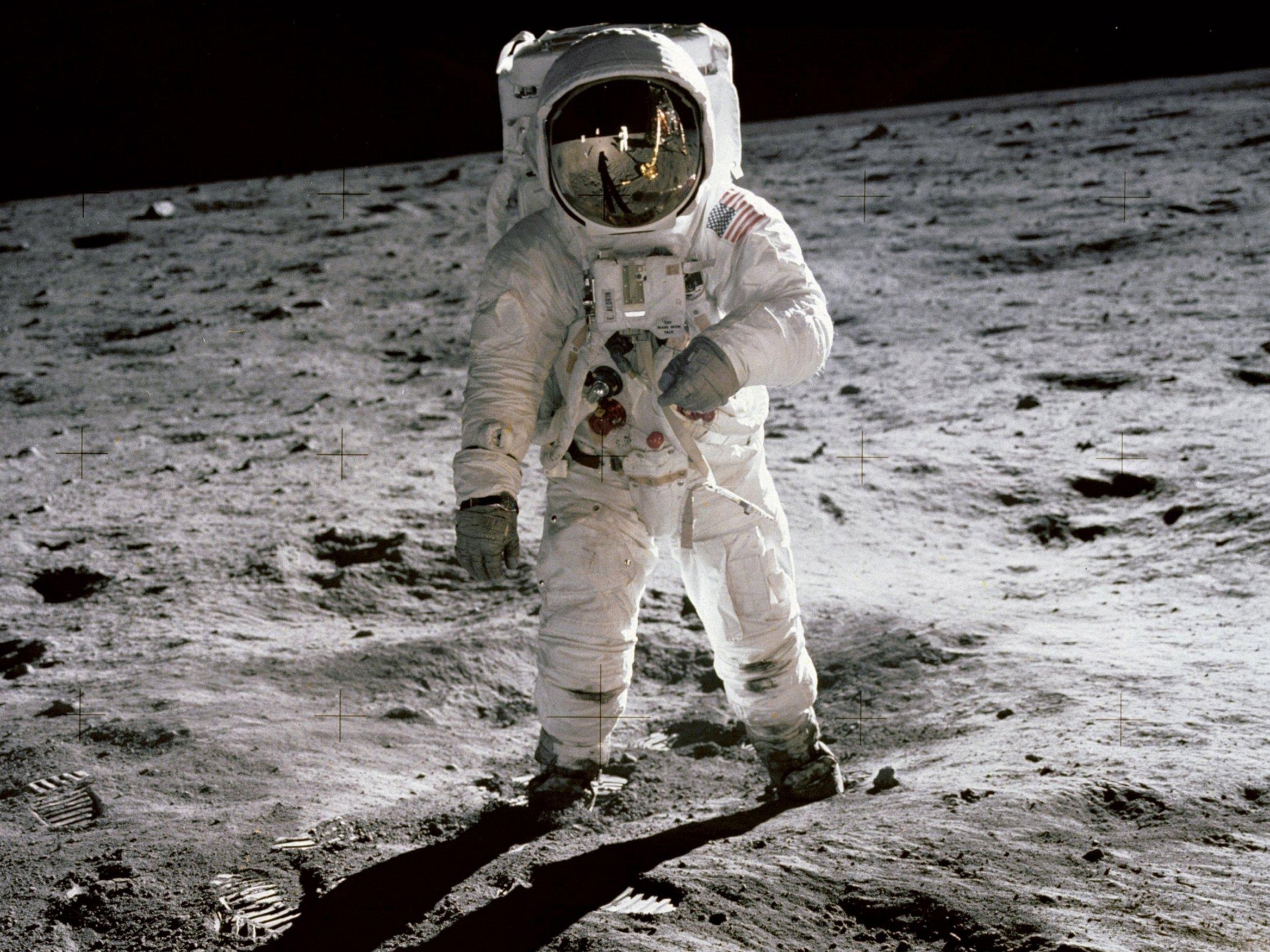

The scene implies that the emotional distances he has to travel on Earth are greater than those which he crossed to the Moon. As with Apollo 13, we know how it’s going to end.īut First Man does so on a carefully crafted note, a plausible hypothesis suggested by biographer Hansen that may have been designed to further humanise the inscrutable astronaut. There is an element of anti-climax about the film’s conclusion. Australia provided tracking stations – famously, Armstrong’s first footfalls on the Moon were transmitted through the Honeysuckle Creek station, outside Canberra.Īustralian space scientist Professor Brian O’Brien, then at Rice University in Texas, designed a dust-detecting experiment that was left on the surface of the Moon. There were numerous international contributions made to the Apollo missions. How could an American mission claim to represent humanity if it included a symbolic act of American colonialism?įortunately, the response of the international community was to celebrate the collective human achievement rather than the national one. The United Nations Outer Space Treaty, ratified by the US just two years before, forbids territorial claims in space. The flag was controversial even at the peak of the Cold War. #proudtobeanAmerican #freedom #honor #onenation #Apollo11 #July1969 #roadtoApollo50 /gApIwLzaJwĬhazelle, the Oscar-winning director of La La Land, said the omission was not political instead he chose to focus on the “unfamous stuff” as well as Armstrong’s experience and character. Some are calling for a boycott over the flag issue.Īrmstrong’s colleague on the Apollo 11 mission, astronaut Buzz Aldrin, has also implied his dissatisfaction with the film in a tweet. The American people paid for that mission,on rockets built by Americans,with American technology & carrying American astronauts.

And a disservice at a time when our people need reminders of what we can achieve when we work together. Republican Senator Marco Rubio is angry that the planting of the US flag – an action symbolising the colonisation of territory – is not shown (although the flag appears more than once). Journalists demand to know how much it is worth, in lives lost and in dollars.īut First Man refocuses the emphasis of the Apollo 11 mission from US nationalism to Armstrong’s personal journey, and this doesn’t sit well with the current far right in Trump’s America.

Many people are shown questioning its value. Embracing the politics of the day, Chazelle recreates the protests around the Apollo missions. The film does not sanitise the space program. It’s a real triumph that First Man (mostly) avoids these cliches and genuinely gives us something new, and somehow more real. Then there’s the passionate flight director, swearing to all who will listen that he’ll get the astronauts home safe. With the notable exception of Hidden Figures, women tend to be shown marooned at home, anguished and accommodating of their physically and emotionally distant husbands. There’s the heroic manly astronaut addicted to risking life and limb. Space films developed a few recurring themes since then. In 1902 Georges Méliès directed and starred in what is considered the first science fiction film, the influential A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage Dans La Lune). We’ve been there before, in filmįor almost as long as there have been moving pictures, we have had movies imagining space flight. The Moon landing is the backdrop, the ultimate distraction from his world of pain, and Gosling plays it beautifully.

Shot often from Armstrong’s perspective, this film is an exploration of apparent emptiness – of space, the Moon, and a man in grief, accustomed to loss and most comfortable when cut off from those closest to him. His lunar quest is tied indelibly to his relationship with his daughter. Armstrong is haunted by the Moon and death throughout the film.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)